2. The flaws of traditional governance

Pitfalls of established hierarchies

Traditional hierarchical systems, from educational institutions to political organizations, have long incentivized people to delegate their power — choices — to chosen delegates.

This process usually takes the form of an election, which by definition is a choice exercised through a vote. As this action is actively presented as participating in governance, it often inflates the actual impact of this systematized process. You get to pick a delegate during a ceremonious institutional event, based on a commitment, that you can only hope will be honored during the following years/months.

The influence of people’s choices, and by extension their lives, fluctuates dramatically — occasionally being exceedingly significant, but in between, diminishing to almost negligible.

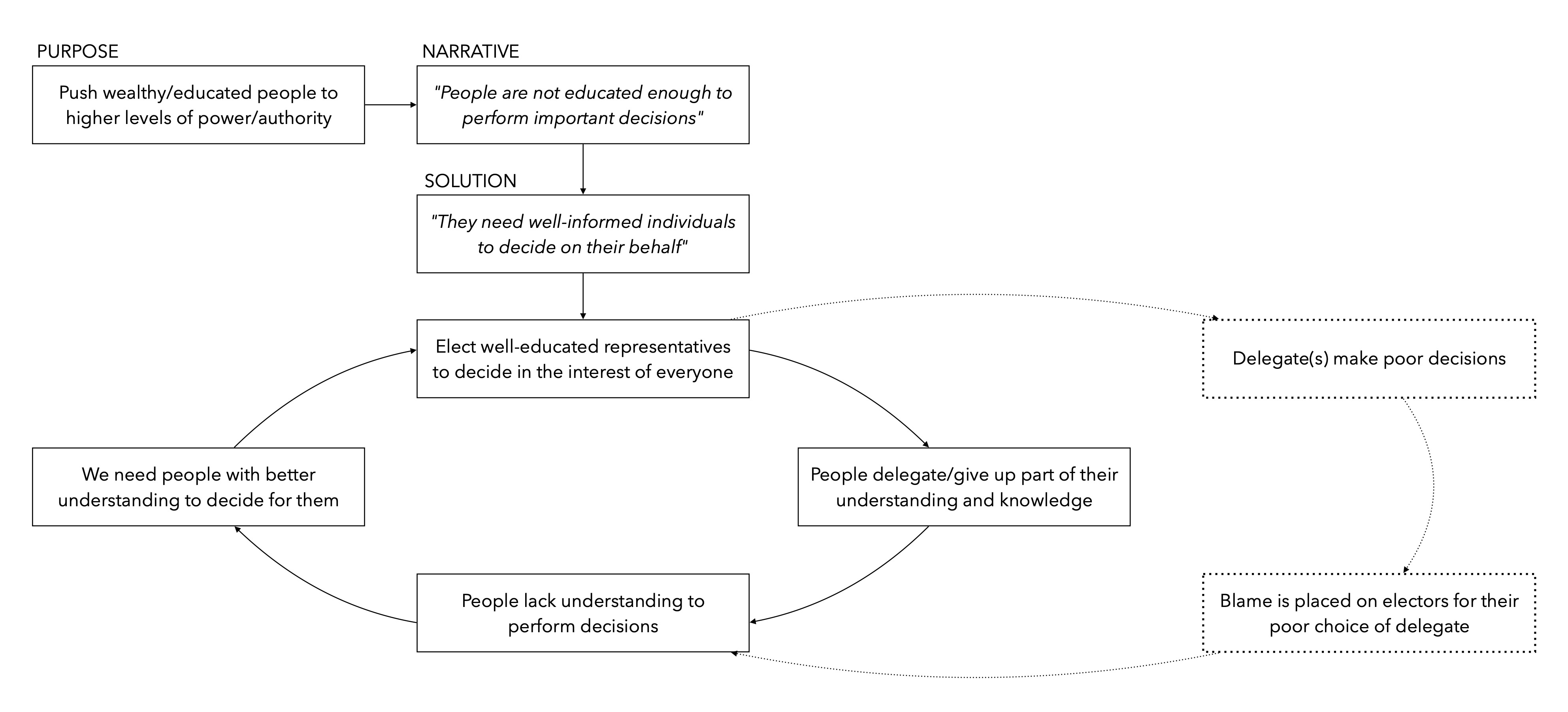

Additionally, constantly delegating our choices means far too frequently delegating our knowledge and understanding as well. Which consequently emphasizes the belief that most people are “not educated enough” to perform decisions. Which incentivize them to delegate to these better informed ones. You get the point.

The vicious cycle of delegation.

The vicious cycle of delegation.

True participation seems more than just electing representatives, but about taking direct responsibility, compelling us to inform ourselves and make mature decisions. However, our established systems often discourage such active engagement.

An illusion of rational compromise in democracy

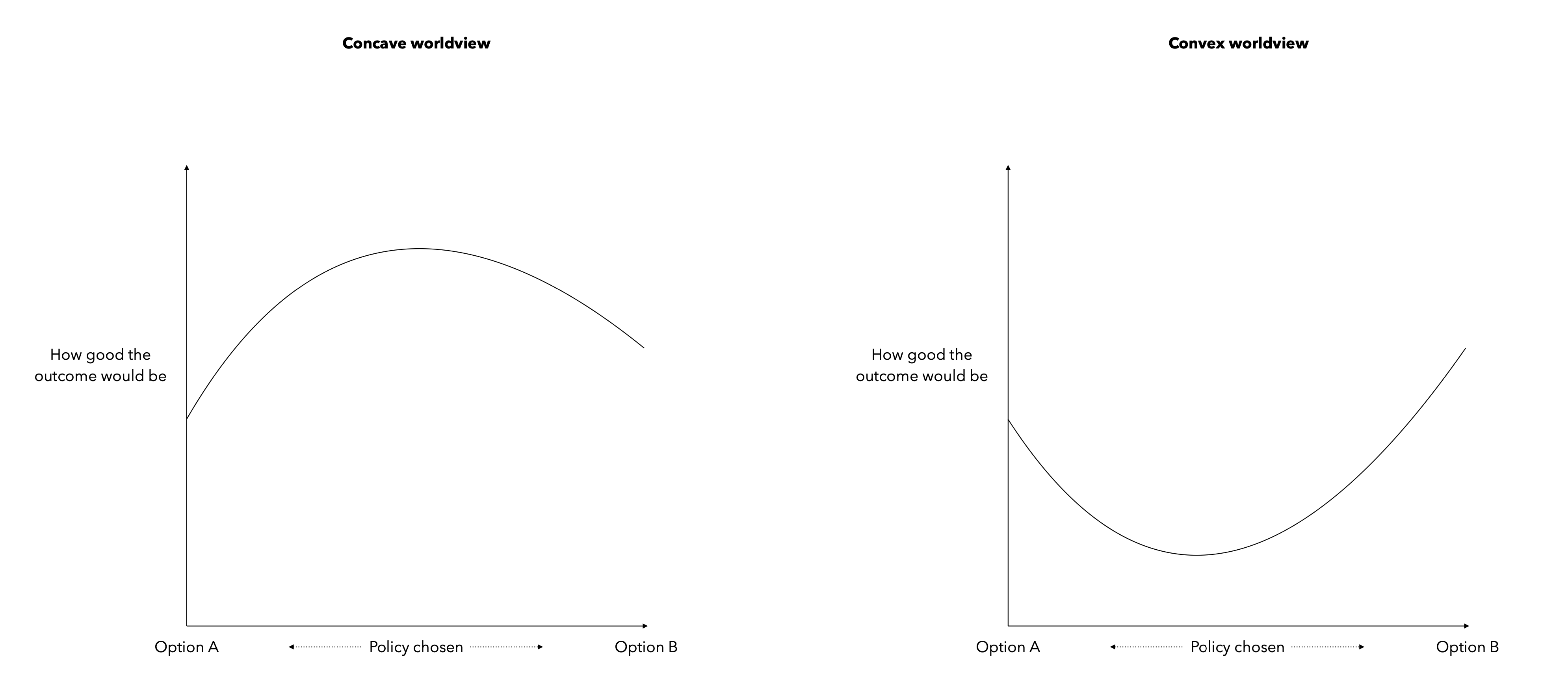

One way of approaching large-scale decisions is to consider them — to borrow words from Vitalik Buterin — as either concave or convex. This applies more extensively to any tradeoff between compromise and purity.

Concave/convex worldview as described by Vitalik Buterin.

Concave/convex worldview as described by Vitalik Buterin.

Given a choice between two alternatives, often both expressed as deep principled philosophies, do you naturally gravitate toward the idea that one of the two paths should be correct and we should stick to it, or do you prefer to find a way in the middle between the two extremes? [Note: respectively convex and concave.]

Vitalik Buterin, "Convex and Concave Dispositions", 2020–11–08, vitalik.ca.

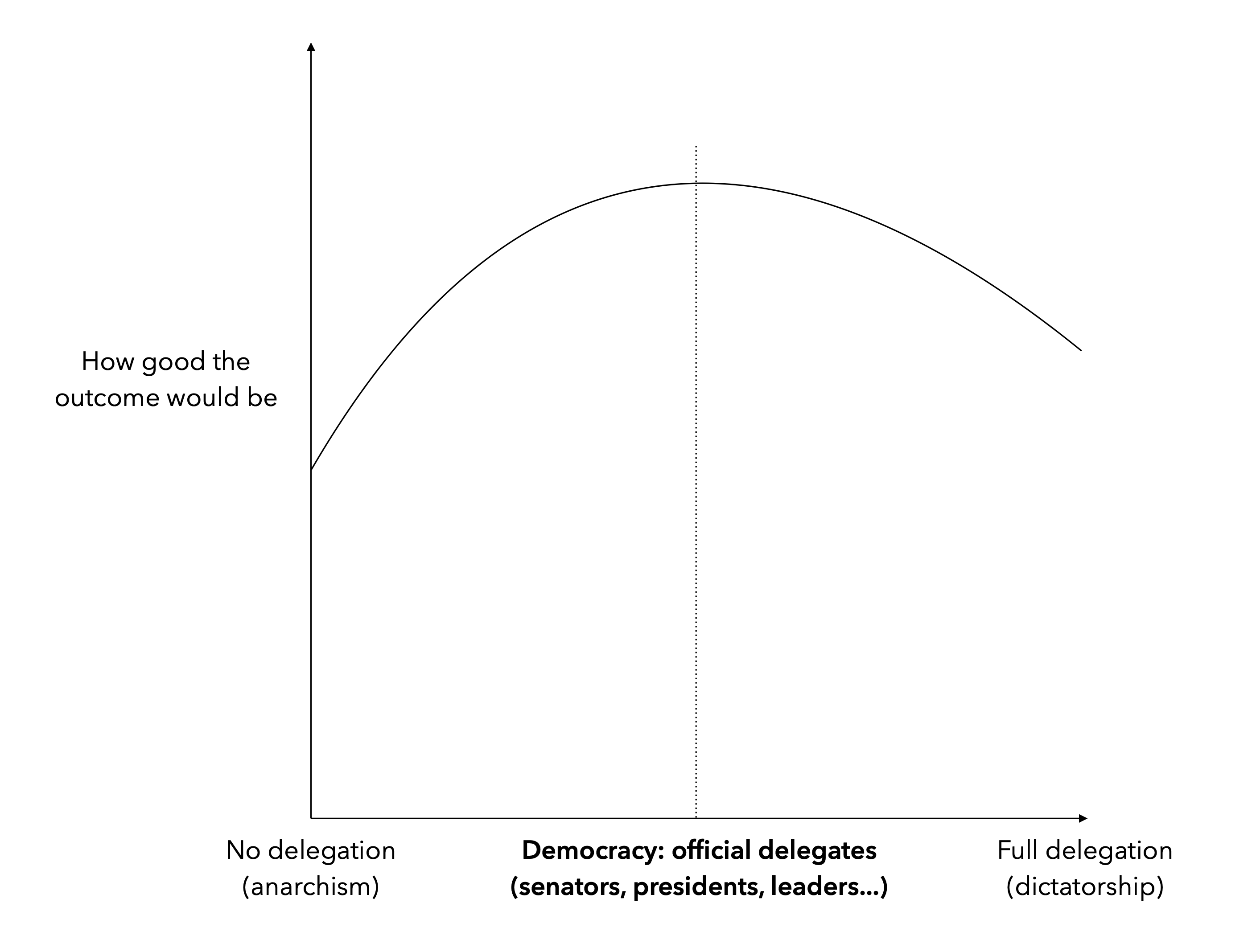

I believe a significant part of modern democracies is designed with a concave disposition. This could be roughly illustrated as follows, assuming that the options are interchangeable; this is not the point here. This conception will be later discussed and iteratively refined.

A concave perspective on modern democracies — as it could be conceived.

A concave perspective on modern democracies — as it could be conceived.

The way we delegate through elections would be (very) roughly considered somewhere between anarchism and dictatorship. Arguably, this is precisely where democracy lies. However, there’s more: governance directly by the population is just as much democracy as it is through representatives — consider participatory democracy as an example.

Delegation’s drawbacks and power struggles

Nevertheless, a significant flaw in the current system is the concentration of decision-making power. Even if it could always be more centralized, most representatives carry heavy responsibilities. Which results in virtually the same symptoms as their absence, i.e. growing indifference — in this case rather due to a decreasing sense of connection with the actual people these delegates represent.

This detachment is not just inefficient; it poses tangible dangers. Decisions made without fully understanding ground realities can — and will — have adverse, widespread impacts.

As a matter of fact, everyone has some kind of purpose, whether it’s personal, collective or, more often than not, both. Representatives are no exception, and by being unable to maintain contact with those around them, they eventually come to rely decreasingly on empathy. At this point, the cherished concept of common good will inevitably be reduced to a merely abstract idea and lose all its essence — an essence that yet provides a safeguard against occasionally misplaced ambition.

This brings us to corruption, which at this stage becomes a conceivable option.