3. Towards a decentralized governance model

Reimagining decision-making in decentralized systems

The emergence of Decentralized Autonomous Organizations (DAOs) presents an alternative to the conventional hierarchical model. In DAOs, authority isn’t centralized; rather, it operates on a horizontal plane. This decentralization is not merely a technological innovation but a societal one. It encourages active participation, challenging the established norms of passivity and detachment fostered by traditional systems — or to phrase it roughly, pushing back against the usual sit-back-and-watch mindset.

Obviously, it’s not without its flaws. Some of them, pointed out by Vitalik Buterin, are reflective of issues we’ve seen in traditional companies, and they echo the challenges inherent to any democratic system — or it’s probably more accurate to say any capitalist system. Examples include insider trading, delegates collaborating for personal gain, or straightforward bribes.

Vitalik points out three typical strategies to combat such corruption: “retroactively punish malicious deciders, proactively filter for higher-quality deciders, add more deciders”. While conventional centralized corporate structures — and by extension, most representative systems — often lean towards the first two solutions, any decentralized system, with its inherent challenges like anonymity, is more likely to push for the third.

The mechanics of decision distribution in decentralized platforms

The decentralized world has less access to such tools: project tokens are likely to be tradeable anonymously, DAOs have at best limited recourse to external judicial systems, and the remote and online nature of the projects and the desire for global inclusivity makes it harder to do background checks and informal in-person “smell tests” for character.

Following this, Vitalik explains how distributing decision-making power among a broader pool not only dilutes the authority of any single participant but also makes collusive acts riskier and more likely to be exposed.

This solution may seem impractical for traditional representative systems; in decentralized platforms, it integrates seamlessly. By distributing choices through collective decision-making, not only is the process more transparent, but it also ensures that each person can be involved, especially on matters that affect their lives. Additionally, this broader participation naturally leads to greater empathy; by being actively involved, individuals gain a deeper understanding of diverse perspectives. This not only results in well-informed decisions but also promotes choices rooted in compassion.

Power distribution: The nuances of scaling and incentivization

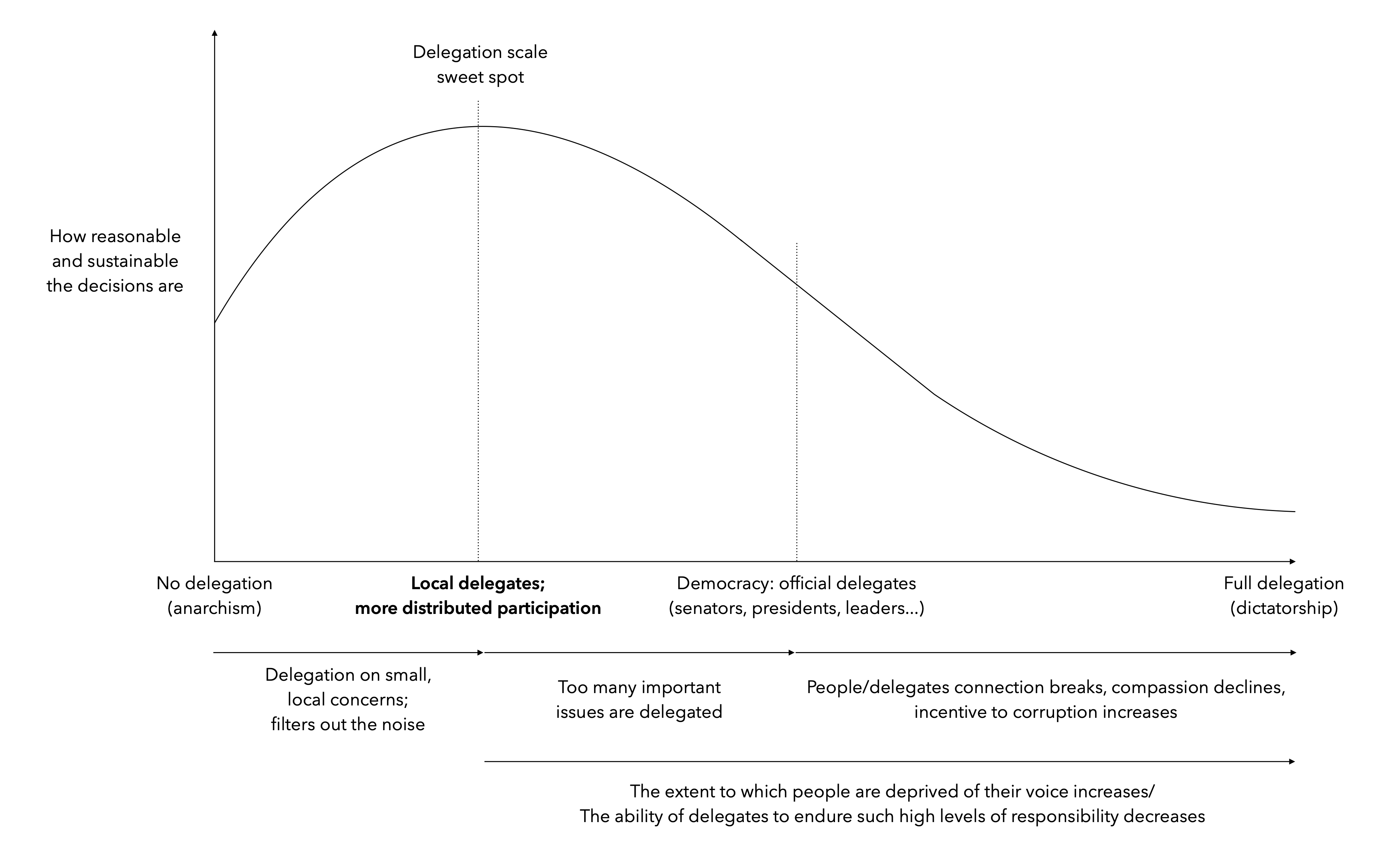

Recalling the earlier concave graph discussion, the issue isn’t with the delegate system itself — it’s its scale. As responsibilities increase, the system seems to grow too large to be effective.

Our current compromise, which positions delegates as the middle ground, might be misconceived. Perhaps the real balance is found between full autonomy and a revised, more limited form of representation — one that engages people more while still benefiting from selective delegation. This doesn’t eliminate delegation but refines it. For instance, we could occasionally trust elected representatives with minor, local issues while actively contributing to wider concerns, and any significant ones. This mechanism ensures that people don’t get paralyzed or burnt out, by filtering out the “noise”.

When we delegate on smaller scale concerns, the allocated power shrinks, which could inherently diminish corruption risks due to lower profitability, lack of significant hierarchical elevation, and more constrained privileges. Additionally, delegates make choices with stakes they cannot circumvent, creating a higher incentive to “stay clean”.

This revised perspective might be represented as an adapted concave graph.

A more detailed concave perspective, with revised positions of sweet spot and current delegation.

A more detailed concave perspective, with revised positions of sweet spot and current delegation.

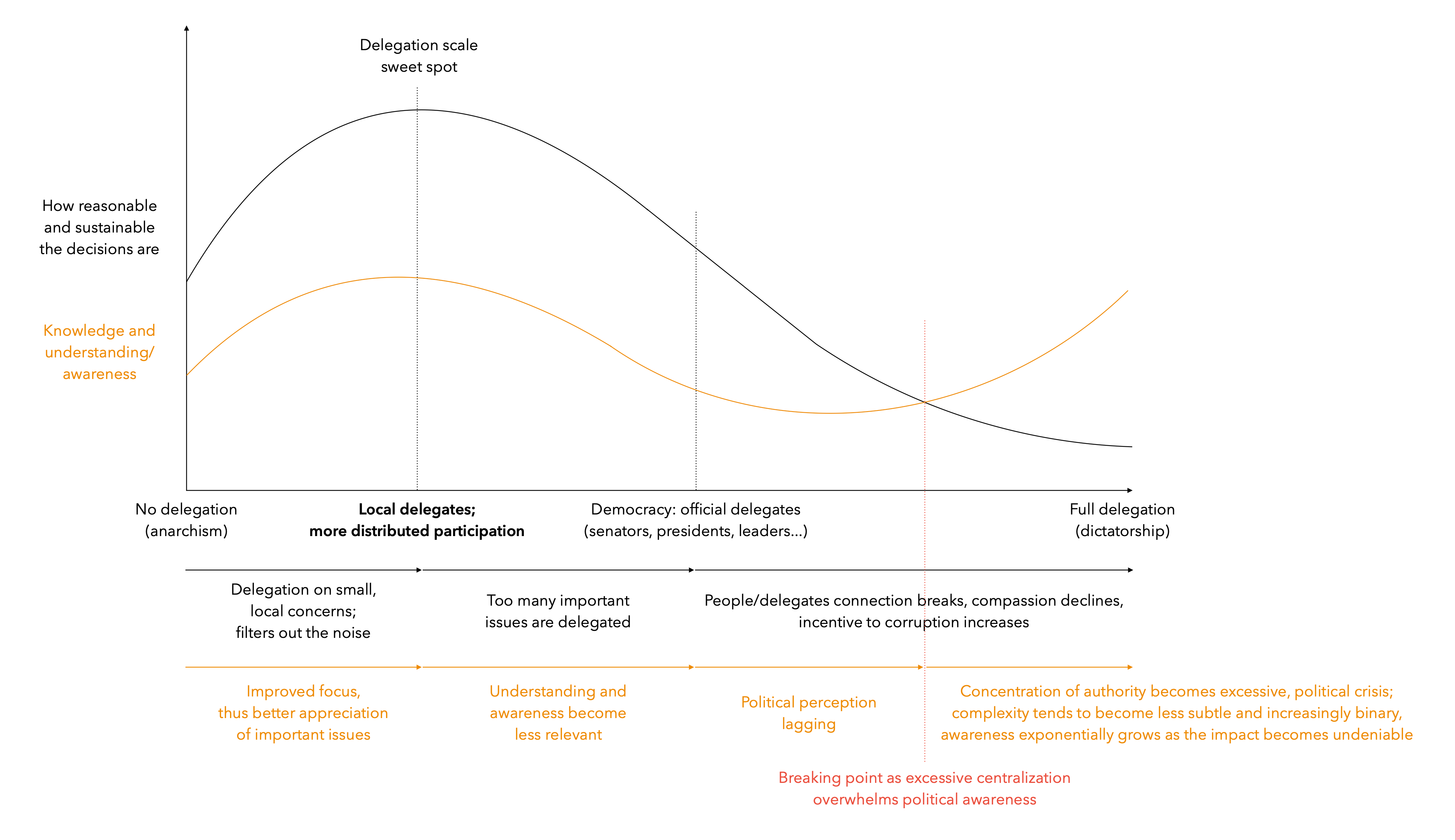

Incidentally, this graph could be enriched to include the knowledge/understanding levels we earlier associated with different scales of delegation.

The same graph further enhanced with knowledge/awareness indicators compared to delegation.

The same graph further enhanced with knowledge/awareness indicators compared to delegation.

At this point, one question that naturally arises when discussing participation is the matter of incentives: what drives individuals to actively engage and contribute?

In Decentralized Finance (DeFi), and most likely in finance altogether, there is a prevailing assumption that financial incentives are essential. This certainly makes sense, given the very nature of such environments. However, this is by no means a requirement for the most diverse political, cultural, educational and institutional systems, as well as for DAOs. To mention only a few incentives:

-

community welfare: people are naturally eager to engage in topics that directly affect them and their immediate community;

-

collective accountability: shared responsibility means any decision reflects collective insight/wisdom;

-

empowerment & validation: having a voice makes people feel acknowledged and in control;

-

educational value: engaging in discussions helps to clarify and better understand different perspectives — a form of continuous learning, that can effortlessly serve as a self-sustaining incentive;

-

strengthening community bonds: active participation can foster tighter-knit communities, especially as most people have a desire to belong and contribute.

These are just some natural incentives generated by such a participative system — in fact, by any democratic system, assuming its scale is reasonably limited.

To the question of scale, a real-world election is difficult to orchestrate; the larger the scale, the more middlemen are required. With blockchain, aside from resource constraints, the underlying technical process stays virtually the same. But this very absence of intermediaries introduces an inherent complexity in ensuring the fairness and accuracy of the data.